Js make a variable global. JavaScript: Variable scope. Features of global objects

This four-part tutorial covers writing quality JavaScript code that is easy to maintain and develop, even if you have to return to the project after a long time.

Write code with the expectation that it will need to be supported

Software bugs have a cost. Their cost is expressed in the time it takes to fix them. Mistakes in publicly launched projects are especially costly. It’s very good if you can fix errors right away, when the code structure is still fresh in your memory, and you can quickly find the problem area. But if you have switched to other tasks and have already forgotten the features of a certain code, then returning to the project will require:

- Time to study and understand the problem.

- Time to understand the code that is causing the problem.

Another problem that affects large projects or companies is that the person who fixes the errors is not the person who creates them (and often is not the person who finds them in the project). Therefore, reducing the time it takes to understand code becomes a critical issue, regardless of whether you wrote the code yourself a while ago or it was written by another developer on your team. The answer to the question will significantly affect both the financial result of the project and the level of satisfaction of the developers, because sometimes it is better to do everything in a new way than to spend hours and days maintaining old, incomprehensible code.

Another fact about software development is that it usually takes longer reading code, not its creation. When the problem is initially stated, the developer focuses and immerses himself in the question, and then sits down and can create significant code in one evening. The code then probably works, but in the natural nature of software products, situations arise that require repeated code revisions. For example:

- Errors are detected.

- New features are added to the project.

- The application must be launched in a new environment (for example, a new browser has appeared).

- The purpose of the code changes.

- The code needs to be completely rewritten or ported to another architecture or programming language.

As a result, several man-hours will be spent writing code, and several man-days reading. Therefore, creating easily maintainable code is critical to the success of an application.

Easily maintainable code has the following characteristics:

- It is easy to read.

- It is well structured and the parts are consistent with each other.

- He is predictable.

- Looks like it was written by one person.

- Documented.

Minimizing the use of global variables

JavaScript uses functions to manage context. Variables declared inside functions are local to them and are not accessible outside the functions. Global variables are declared outside functions or simply used without declaration.

Every JavaScript environment has a global object that is used outside of functions. Every global variable you create becomes a property of the global object. In browsers, for convenience, there is an additional property on the global object called window that (usually) points to the global object itself. The following code shows an example of creating and accessing global variables in the browser environment:

Var myglobal = "hello"; console.log(myglobal); // "hello" console.log(window.myglobal); // "hello" console.log(window["myglobal"]); // "hello" console.log(this.myglobal); // "hello"

Problems with global variables

The problem with global variables is that they will be available throughout the JavaScript code of your application or page. They are in the global namespace, and there is always a chance for naming collisions, where two different parts of the application define global variables with the same name but for different purposes.

Also, the web page usually includes code written by other developers. For example:

- Other JavaScript Libraries.

- Scripts from advertising partners.

- Code for user tracking and analytics.

- Various widgets, buttons and plugins.

Let's say that in one of the third-party scripts a global variable is defined, which is called, for example, result . Then you define another global variable in one of your functions and call it result . As a result, the last declaration of the result variable will override the first, and the third-party script may stop working.

Therefore, to successfully combine different code on a single page, it is important to use as few global variables as possible. In this matter, the use of the var directive when declaring variables plays a significant role.

Unfortunately, it's very easy to unintentionally create a global variable in JavaScript due to two features of it. First, you can use a variable without declaring it. Second, JavaScript has a definition of implied global, which means that any undeclared variable becomes a property of the global object (and will be accessible as a properly declared global variable). For example:

Function sum(x, y) ( // bad: implied global result = x + y; return result; )

In this code, the result variable is used without declaration. The code works fine, but after calling the function you will end up with another result variable in the global namespace, which can lead to problems.

The minimization rule is to define variables using the var directive. Below is an improved version of the sum() function:

Function sum(x, y) ( var result = x + y; return result; )

Another bad option for creating implied globals is chaining a value assignment within a var declaration. In the following example, variable a will be local and variable b will be global, which is probably not the intent of the code creator:

// bad, don't use function foo() ( var a = b = 0; // ... )

If you're surprised by what's happening, it's a matter of right-to-left calculations. The expression b = 0 is executed first, and therefore the variable b will not be declared. The return value of the expression will be 0, and it is assigned to a new local variable a, which is declared by the var directive. This definition of variables is equivalent to the following notation:

Var a = (b = 0);

If you have already declared the variables, then the chained representation will work fine and will not create unwanted global variables:

Function foo() ( var a, b; a = b = 0; // both variables are local )

Another reason to avoid using global variables is code portability. If you plan to run the code in a different environment, then global variables may overwrite objects that are not in the original environment (so it may seem that the name you use is safe).

Side effect of forgotten var declaration

There is a slight difference between explicitly defined and implied global variables. It is the ability to delete a variable using the delete operator:

- A global variable declared by a var declaration (created in a program outside of functions) cannot be deleted.

- An implied global variable created without declaration (regardless of where it was created) can be deleted.

Technically, an implied global variable is a property of the global object, not a variable. Properties can be deleted using the delete operator, but variables cannot:

// define three global variables var global_var = 1; global_novar = 2; // bad (function () ( global_fromfunc = 3; // bad )()); // Trying to delete delete global_var; // false delete global_novar; // true delete global_fromfunc; // true // Checking deletion typeof global_var; // "number" typeof global_novar; // "undefined" typeof global_fromfunc; // "undefined"

Accessing a Global Object

In browsers, the global object is available at any point in the code through the window property (unless you do something special or unexpected, such as declaring a local variable named window). But in other environments, this convenient property may be available in a different way (or even not available to the programmer at all). If you need to access the global object without using the window identifier, then you can use the following method at any nested function namespace level:

Var global = (function () ( return this; )());

Thus, it is always possible to access the global object, because within a function that is called as a function (and not as a constructor with a new declaration), this always points to the global object.

Single declaration template var

Using a single var declaration at the top of your function is a very useful practice. This method has the following advantages:

- Provides a single place to declare all local variables of a function.

- Logical errors are prevented when a variable is used before it is declared.

- Helps to remember to declare local variables and hence reduces the number of global variables.

A template with one var declaration looks like this:

Function func() ( var a = 1, b = 2, sum = a + b, myobject = (), i, j; // Function code... )

You use a single var declaration to declare multiple variables, separated by commas. An excellent addition would be to initialize variables with source data when declaring them. This prevents logical errors (all uninitialized variables are set to undefined by default) and improves code readability. When you look at the code later, you will be able to determine the purpose of a variable by its initial value (for example, you will immediately see that it is an object or an integer).

You can also perform an operation on variable declaration, such as sum = a + b from the previous example code. Another working example is DOM manipulation. You can assign references to DOM elements to local variables when declaring:

Function updateElement() ( var el = document.getElementById("result"), style = el.style; // perform operations with el and style... )

Lifting: problem with scattered var declarations

JavaScript allows multiple var declarations anywhere in a function, and they act the same regardless of placement. This feature is known as "lifting". This behavior can lead to logical errors when you use a variable and then declare it for later function code. For JavaScript, since a variable is in the same namespace (in the same function), it is assumed to be declared, even if they are used before the var directive. For example

// bad myname = "global"; // global variable function func() ( alert(myname); // "undefined" var myname = "local"; alert(myname); // "local" ) func();

In this example, the first call to alert() is expected to produce the message “global” and the second call to “local.” A reasonable expectation, since the local variable myname is not declared on the first call, and the function must use the global variable myname . But in reality, things work differently. The first call to the alert() function will return "undefined" because myname is treated as a declared local variable in the function (although the declaration will come later). All variable declarations are hoisted to the top of the function. Therefore, to avoid this type of error, you need to declare all variables at the top of the function.

The previous example will act as if it were implemented like this:

Myname = "global"; // global variable function func() ( var myname; // same as -> var myname = undefined; alert(myname); // "undefined" myname = "local"; alert(myname); // " local" ) func();

It's worth mentioning that the actual implementation of the code is more complex. There are two stages of code processing. In the first stage, variables, function declarations, and formal parameters are created, and the context is defined. In the second stage, code is executed, functions are evaluated, and unqualified identifiers (undeclared variables) are created. But for practical application, the concept of lifting can be used, which describes the behavior of the code well.

Hello! Today we will talk about the scope of variables (read what a variable is). The fact is that when you create a variable in a function and its name matches the name of a variable outside the function, then there can be various interesting situations related to the global and local scope of the variable.

This is exactly what we will deal with in this lesson.

Global variable

Global variables include all variables that you create outside of the function. And you definitely need to create a variable using the var keyword; if you don’t do this, the variable will be visible everywhere in the program and, moreover, if strict mode is enabled, it will cause an error. In order to enable strict mode, just write the line “use strict” at the beginning of your script. This will tell the JavaScript interpreter to strictly adhere to the JavaScript standard. Here is an example using a global variable

Var a =6; //global variable function double() ( return alert(a*a); //using a global variable ) double();

In the example, a global variable a is declared, which is assigned the value 6. In the function, we can access this variable and even change its value, and this value will change everywhere.

Let's look at an example where the value of a global variable is changed in a function, and then we access the global variable outside the function and see the value that was set to it in the function itself.

Var a =6; function double() ( a = 5; //change the value of the global variable in the function return alert(a*a); ) double(a); //call the function document.write(a); //global variable value

As you can see from the example, if you change the value of a global variable in a function, it remains with it everywhere, both in the function and outside it.

Local variable.

When you declare a variable in a function, it becomes local and can only be accessed from within the function. It is worth noting that if/else , for, while, do...while statements do not affect the scope of variables.

So it turns out that within a function you can access a global variable, but globally outside the function you cannot access a local variable created in the body of the function. Let's look at an example.

Function double() ( var a =6; return alert(a*a); ) double(); document.write(a); //trying to access a local variable

In the example, the variable is not declared globally, but rather declared in the function, that is, locally. Then we call the function and try to access the local variable, but as a result nothing happens, and in the console we see an error that the variable is not defined.

And the last option is when both a global variable and a local one with the same name are created, what will happen then. Let's see an example.

Var a =7; function double() ( var a =6; return alert(a*a); ) document.write(a);

As you can see, here a different variable is created in the function, despite the fact that its name coincides with the global one and it is the local variable that will be available in the function; it will not be able to overwrite the global one, which is what this example shows.

What conclusion can be drawn from all this? This means trying to use variables with different names both inside and outside the function. But you need to know about local and global scopes.

Results.

A variable created outside a function is global.

From a function you can access a global variable and change its value.

Variables

Declaring Variables

Before you can use a variable in JavaScript, it must be declared. Variables are declared using a keyword var in the following way:

Var i; var sum;

By using the var keyword once, you can declare multiple variables:

Declaring variables can be combined with their initialization:

Var message = "hello"; var i = 0, j = 0, k = 0;

If no initial value is specified in the var statement, then the variable is declared, but its initial value remains undefined until it is changed by the program.

If you have experience using programming languages with static data types, such as C# or Java, you may notice that variable declarations in JavaScript lack a type declaration. Variables in JavaScript can store values of any type. For example, in JavaScript you can assign a number to a variable, and then assign a string to the same variable:

Var i = 10; i = "hello";

With the var statement, you can declare the same variable more than once. If the repeated declaration contains an initializer, then it acts like a regular assignment statement.

If you try to read the value of an undeclared variable, JavaScript will generate an error. In the strict mode provided by the ECMAScript 5 standard, an error is also raised when attempting to assign a value to an undeclared variable. However, historically, and when not executed in strict mode, if you assign a value to a variable that is not declared with a var statement, JavaScript will create that variable as a property of the global object, and it will act much the same as a correctly declared variable. This means that global variables need not be declared. However, this is considered a bad habit and can be a source of errors, so always try to declare your variables using var.

Variable scope

The scope of a variable is the part of the program for which the variable is defined. A global variable has global scope - it is defined for the entire JavaScript program. At the same time, variables declared inside a function are defined only in its body. They are called local and have local scope. Function parameters are also considered local variables, defined only within the body of that function.

Within a function body, a local variable takes precedence over a global variable of the same name. If you declare a local variable or function parameter with the same name as a global variable, the global variable will actually be hidden:

Var result = "global"; function getResult() ( var result = "local"; return result; ); console.log(getResult()); // Display "local"

When declaring variables with global scope, the var statement can be omitted, but when declaring local variables, you should always use the var statement.

JavaScript has three scopes: global, function, and block scope. Variable scope is a section of a program's source code in which variables and functions are visible and can be used. The global scope is also called top-level code.

Global variables

A variable declared outside a function or block is called global. The global variable is available anywhere in the source code:

Var num = 5; function foo() ( console.log(num); ) foo(); // 5 console.log(num); // 5 ( console.log(num); // 5 )

Local variables

A variable declared inside a function is called local. A local variable is accessible anywhere within the body of the function in which it was declared. The local variable is created anew each time the function is called and destroyed when exiting it (when the function completes):

Function foo() ( var num = 5; console.log(num); ) foo(); // 5 console.log(typeof num); //undefined

A local variable takes precedence over a global variable of the same name, meaning that inside a function the local variable will be used rather than the global one:

Var x = "global"; // Global variable function checkscope() ( var x = "local"; // Local variable with the same name as the global one document.write(x); // Use a local variable, not a global one) checkscope(); // => "local" Try »

Block Variables

A variable declared inside a block using the let keyword is called a block variable. A block variable is accessible anywhere within the block in which it was declared:

Let num = 0; ( let num = 5; console.log(num); // 5 ( let num = 10; console.log(num); // 10 ) console.log(num); // 5 ) console.log(num) ; // 0

Re-announcement

If you use the var keyword to re-declar a variable with the same name (in the same scope), then nothing will happen:

Var a = 10; var a; console.log(a); // 10

If the re-declaration is accompanied by an initialization, then such a statement acts like a normal assignment of a new value:

Var a = 10; var a = 5; // Same as a = 5; console.log(a); // 5

If you use the let keyword to re-declar a variable with the same name (in the same scope), an error will be thrown:

Var a = 10; let a; // Error.

Scope chain

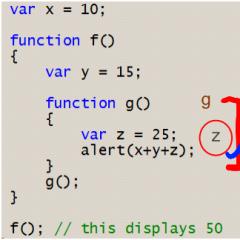

Consider the following example:

Var num = 5; function foo() ( var num2 = 10; function bar() ( var num3 = 15; ) )

This code has three scopes: global, foo() function scope, and bar() function scope. The global scope defines the variable num and the function foo() . The scope of the foo() function defines the variable num2 and the function bar() , and the variable num from the global scope is also available in it. The scope of the bar() function contains one variable, num3, which is only accessible within the bar() function. The bar() function's scope also has access to variables from the other two scopes because they are its parents. The scope chain for this example is shown in the figure below:

In the figure, different visibility areas are shown by rectangles of different colors. The inner scope in a chain of scopes has access to everything from the outer scopes, but the outer scopes have access to nothing from the inner scopes.

The scope chain is ordered. The interpreter looks outward, not inward, for identifiers in the scope chain. This means that the name search starts from the scope where the identifier was accessed. If the ID name is found, the search stops. If a name cannot be found in the current scope, a search is performed in the next (outer) scope, etc. Thus, the identifier from the scope in which it was found will be used. If the identifier is not found in any of the scopes, JavaScript will generate an error:

Var str = "global"; var num = 5; function foo() ( var str = "local"; // Using local variable str num = 10; // Using global variable num // alert(x); // Error. Variable x is not in any scope ) foo( ); alert(str); // "global" alert(num); // 10

If you assign a value to an undeclared variable in the body of a function, then at the time the function is called, if there is no variable with the same name in the global scope, a new global variable will be created:

Function foo() ( num = 2; ) foo(); // Created a new global variable num alert(num); // 2

Rise of advertisements

In JavaScript, declared variables are accessible anywhere relative to their scope, meaning that variables are visible even before they are declared in code. This feature of JavaScript is informally called hoisting: the program code behaves as if variable declarations were implicitly hoisted (without initialization) to the very top of their scope.

Consider the following code snippet:

Var str = "global"; function foo() ( alert(str); // undefined var str = "local"; alert(str); // "local" ) foo();

Looking at the code, you would think that the first alert should print the string "global" because the declaration of the local variable str has not yet been done. However, it actually outputs the value undefined . By raising declarations, the function above is equivalent to the implementation below, in which the variable declaration is raised to the beginning of the function:

Function foo() ( var str; // Declaration of a local variable at the beginning of the function alert(str); // Here it is available, but not initialized str = "local"; // Here it is initialized alert(str); // And here it has the expected value - "local")

The same applies to the global scope, a variable declared at the bottom is accessible at the top:

Alert(num); // undefined var num = 10; alert(num); // 10

Variables serve as "containers" for storing information.

Do you remember High School Algebra?

Do you remember school algebra? x=5, y=6, z=x+y

Do you remember that a letter (eg x) could be used to store a value (eg 5), and that you could use the information above to calculate that the value of z is 11?

These letters are called variables, and variables can be used to store values (x=5) or expressions (z=x+y).

JavaScript variables

Just like in algebra, JavaScript variables are used to store values or expressions.

The variable can have a short name, such as x, or a more descriptive name, such as carname.

Rules for JavaScript variable names:

- Variable names are case sensitive (y and Y are two different variables)

- Variable names must begin with a letter or underscore

Comment: Since JavaScript is case sensitive, variable names are also case sensitive.

Example

The value of a variable can change while the script is running. You can reference a variable by its name to display or change its value.

Declaring (Creating) JavaScript Variables

Creating variables in JavaScript is more commonly referred to as "declaring" variables.

You declare JavaScript variables using a keyword var:

After following the suggestions above, the variable x will contain the value 5 , And carname will contain the value Mercedes.

Comment: When you assign a text value to a variable, enclose it in quotation marks.

Comment: If you declare a variable again, it will not lose its value.

JavaScript Local Variables

A variable declared inside a JavaScript function becomes LOCAL and will only be available within this function. (the variable has local scope).

You can declare local variables with the same name in different functions because local variables are recognized in the function in which they are declared.

Local variables are destroyed when the function exits.

You'll learn more about functions in subsequent JavaScript lessons.

JavaScript Global Variables

Variables declared outside the function become GLOBAL, and all scripts and functions on the page can access them.

Global variables are destroyed when you close the page.

If you declare a variable without using "var", the variable always becomes GLOBAL.

Assigning Values to Undeclared JavaScript Variables

If you assign values to variables that have not yet been declared, the variables will be declared automatically as global variables.

These suggestions:

You'll learn more about operators in the next JavaScript lesson.